Steven Peck – Green Roofs for Healthy Cities

Steven Peck is dedicated to creating greener, healthier & resilient cities with nature & urban agriculture.

Singapore

Cassidy Green November 10, 2020

Jason Pomeroy, world-renowned architect and scholar leading in sustainable design, uses a unique approach of evidence-based interdisciplinary design to create long-term building solutions that are resilient in the face of a changing climate. As a sustainable architect, researcher, academic, and author, Pomeroy thinks beyond the typical social, economic and environmental triple bottom line that most scholars guide their research on. His quest for a balance between creative design for the built environment and fact and reason has led him to create thought-provoking projects such as the first zero-carbon house in Asia and ALICE, a multi-tented smart eco-business park in Singapore.

Passionate about sharing knowledge to help halt the disastrous effects of climate change, Mr. Pomeroy created his own architecture academy based on sustainable principles and research. He has authored four books, travels around the world to give keynote speeches on sustainable design, and stars in multiple television series that present the emerging smart cities of the world.

Mood of Living : Where were you born and raised?

Jason Pomeroy : I was born in London, UK, to a British father and a Malaysian-Chinese mother; and this was where I was raised. The first experience of the wider World, outside the comfort of my home, was a lovely little walled garden. This humble space provided the natural play-pen in which I would learn to ride my bike, set up a wig-wham tent, and get close and personal to the rich flora and fauna that my mother lovingly attended. Given my parents, I led quite a peripatetic lifestyle; flitting between London, Kuala Lumpur and the occasional European city during the course of the year which, thankfully, gave me a thirst for wider experiences and an awareness of a wide range of cultures.

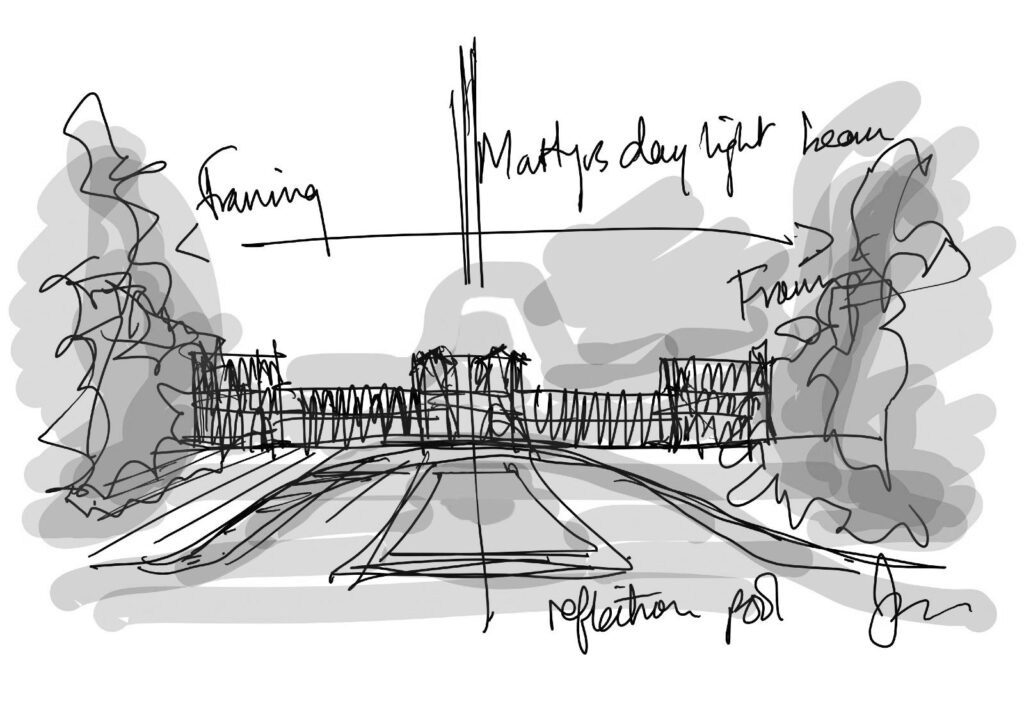

Jason P Secretariat Yangon sketch – Pomeroy-Studio

MoL: What was your path to becoming an environmental architect?

JP: It started as a child! The natural habitat was an intrinsic part of my youth, but was infused by a passion for the urban habitat at the tender age of 8 years old, when my father took me to St. Pauls Cathedral in London. I was told in humbling terms that the role of the architect was to orchestrate the shaping and design of the built environment, and that Sir Christopher Wren was the architect of this magnificent structure that stood in front of me. I was later to learn that he was not only an architect but also an astronomer, physicist, surveyor and mathematician – a multi-faceted individual who ignited my passion for architecture and its inter-disciplinary nature of problem solving.

MoL: Where did you go to school and what did you study?

JP: I studied at the Canterbury School of Architecture for under graduate and post graduate degrees in architecture; my Masters degree in ‘Interdisciplinary Design for the Built Environment’ at Cambridge University, and my PhD in ‘the role of skycourts and skygardens as alternative social spaces for the 21st century at Westminster University. My years studying at Cambridge were most enjoyable – it’s a place made richer by the buildings designed by the very same man that influenced me as a child, i.e. Sir Christopher Wren. This time I had the chance of viewing his creations from a different perspective – that of being able to harness the benefits of natural light and ventilation and the appropriate orientation of buildings to reduce the negative environmental impacts.

POG Project

MoL: At what point in your life did you move from England to Singapore?

JP: At the age of 31 I was recruited into the London office of Broadway Malyan, an international firm of architects, urbanists and designers, with the role of leading the sustainable agenda and ensuring the delivery of sustainable design solutions across the practice. With a burgeoning portfolio of International works and expansion plans overseas, I was seconded after 2 years to Singapore and established an Asian presence for the company at 33. Over the next 5 years, we grew the studio from a team of 3 to 65, leading it to become a successful design practice in Asia, and in the process leave a legacy of sustainable design projects in the region. Projects of note transcended scale and discipline, and ranged from the macro-scale of regional city planning, such as Vision Valley Malaysia – an 80,000-acre Network Garden City extension of Kuala Lumpur; to the micro scale of the first zero carbon house in Asia, called the Idea House.

MoL: How does Pomeroy Studio differ from other architectural firms? Where is its home base? Where are most of your projects located?

JP: I think a belief in the virtues of collaboration between designers and researchers makes us unique, and has led the studio to comprise of masterplanners, landscape architects, architects, interior and graphic designers, as well as environmental consultants and academics. A knowledge base that applies a rigorous academic approach to quantitative and qualitative research complements an interdisciplinary design process that lies at the foundation of our creative design decision-making. This has allowed the Studio, based in Singapore, to generate award-winning, people-centred places that continually push the envelope of design and research, and deliver innovative sustainable solutions across built environment sector and discipline that range from the micro scale of dwellings to the macro scale of whole cities in Asia, Middle East and Europe. This unique approach, which we call Evidence-Based Interdisciplinary Sustainable Design (or E-BISD for short), rings true to the Studio’s motto of balancing a ‘creative vigour with an academic rigour’.

MoL: What and/or who inspired you to become a sustainable architect?

JP: Perhaps it was the polarized environments of Canterbury and Cambridge that acknowledged my quest for balancing creative design for the built environment, with an objective approach to generating design solutions that were based on fact and reason. If there was a commonality in these early educational influences, it lay in how both institutions provided a balance between the creative and the academic, and my absorption into critical regionalism and environmental design before the notion of geographically sensitive green architecture became en vogue. My time at Canterbury was marked by a respect of low-energy, passive ‘lean’ design solutions, as well as past historical precedents and cultural influences. An interest in the abstraction and reinterpretation of social and cultural practices, set within an environmental context, drew me to the design works of Charles Correa and Ken Yeang and the writings of Kenneth Frampton. This was in the interests of creating architecture with a regionalist identity that bore the essence of a culture, yet did not cross into the realms of pastiche.

MoL: In what ways do your projects follow the Sustainable Development Goals? How do you track the success of these goals? What are the challenges and rewards of being committed to sustainability in your field?

JP: Arguably, I have spent much of my professional and academic career helping to redefine sustainability and go beyond the often-accepted balance between social, economic and environmental principles. Afterall, world population is projected to exceed 9 billion people by 2050. Developing countries will have the biggest growth, with a projected rise from 5.6 billion in 2009 to 7.9 billion in 2050. This inevitably results in 3 issues – the heightened social and cultural transmigration as a response to urbanisation and rising land prices; the privatisation of space and the consequent depletion of those environments that once fostered social interaction; and the continued rise in urban temperatures that contribute to climate change. A spatial, cultural and technological sustainability seem just as an important set of parameters that should be considered alongside the widely accepted ‘triple bottom line’ to create more robust urban habitats that reinforce the edict of ‘people, profit and planet’. This has resulted in a ‘mantra’ that we seek to instil in our projects. Knowing that we are positively shaping people and places is immensely satisfying.

Optimma Residences, CaSoBe Resort Interior, Aurel Sanctuary – Pomeroy Studio

MoL: With such a wide variety of projects you’re working on, how or where do you find inspiration to create new, innovative structures that improve the quality of life of the people working and residing within them?

JP: I tend not to look at other architects work as my studio has quite a unique ‘style’ that is born out of a rigorous questioning based on the social, economic, environmental, spatial, cultural and technological needs of a people and a place. What is important is the process, which we often call the 3D’s – the ability to Distill, Design and Disseminate. We distill lessons from the past, and these could very well be social, cultural or natural influences that we rigorously study and draw from as a source of inspiration. An example would be our ‘Casobe’ project in the Philippines. We drew inspiration from the galleon trade heritage between Manila and Acapulco and ‘distilled’ a nautical theme that spoke of such a narrative. We then designed the masterplan, landscape, architecture, interior, and branding that drew upon the narrative. The final ‘D’ of ‘disseminate’ comes in the form of how we shared that knowledge or story to the wider audience – be that through books, TV or simply delivering the project for people to inhabit and enjoy.

MoL: Of all the projects you’ve worked on, which one is your favorite or the most important? Why?

JP: This is a tough question, as I love all my projects! They are all my babies that have been nurtured in their own unique way and it would be unfair to show preference. Also, the projects are not just cities, buildings and landscapes: they include my books, my lectures and my TV series, which I similarly nurture and love. But if I had to pick one, I’d have to say that, in 2010, I designed Asia’s first carbon-neutral prototype home, called the Idea House. This home drew on many of the passive design principles present in the traditional Malay Kampong homes, which we extensively studied and reinterpreted to create a super low energy, passive designed house. We then incorporated modern green technologies, resulting in a home that is carbon zero. We also experimented with modular construction – resulting in quicker construction times, lower costs and less on-site disruption. Lastly, we ensured that the design was culturally sensitive – permitting the expansion and contraction of the interior spaces to allow for extended family living and built in features that were conducive to sustainable Asian tropical living for the 21st century. This project also ‘gave birth’ to my first book and was also my first foray in front of the cameras. So, I have a lot to be thankful for in this project.

Idea House

MoL: Tell us about the creation of Pomeroy Academy. What is it and what inspired you to create it? Other than Pomeroy Academy, what schools do you teach at?

JP: Pomeroy Academy are educators and researchers of sustainable built environments and provide training and educational courses in the field of sustainability for the built environment industry. They also undertake research in the fields of zero carbon development, the role of urban greenery, smart and sustainable cities, modular construction and cultural sustainability and conservation. The courses created are specialist in nature and are focused on the process of designing more sustainable built environments through an evidence-based approach. I founded the academy given my interests in sharing sustainable design knowledge with an industry that is increasingly needing to respond to climate change; and a broader audience who are increasingly worried about the state of our planet. This has led to my professorships / appointments at Nottingham University, James Cook University, King Saud University and Cambridge University. We are pleased to support an internship programme at Pomeroy Studio, and extend our congrats to Dixi Mengote-Quah, the winner of the inaugural 2020 Pomeroy Academy Scholarship for Interdisciplinary Design for the Built Environment (IDBE) in Cambridge University.

Jason Pomeroy Portrait, Venice Masterclass

MoL: Pomeroy Studio combines architectural design and research. What does the research entail? How do you marry your architectural vision and research to create innovative designs?

JP: The pursuit of fact and reason through research feeds our pursuit of designing people-centric sustainable built environments. For instance, my book, The Skycourt and Skygarden: greening the urban habitat, has influenced our innovations in skyrise urban greenery and the role skycourts and skygardens play as social spaces in high density cities. Pod Off-Grid built upon my zero-carbon research of the Idea House and was an exploration into floating zero-energy waterborne communities. This has recently spurred our interest and further research into closed-loop floating solar and agricultural farming on water. My latest book is a compendium of essays from various designers, academics and administrators who contribute their thoughts on the interrelationship between culture and innovation. The book is titled, Cities of Opportunities: connecting culture and innovation, has since led to the planning of a TV series that explores the very same subject matter and will allow us to touch a broader audience.

Aquarius Business-Park, Azure North Residences, Digital Hub Masterplan, EduCity Masterplan, Kallang Alive Masterplan -Pomeroy Studio

MoL: As a professor and researcher, do you find sustainable architecture to be an interdisciplinary subject? If so, how?

JP: The creation of cities, buildings and landscapes is not the will of a single individual or profession but an interdisciplinary effort of multiple professionals (engineers, surveyors, planners, for example) as well as stakeholders and legislators pulling together to create what is hopefully a sustainable built environment. Couple this with the fact that sustainability means different things to different people depending on their industry and you have an added complexity which, for me, adds to the enjoyment in the process of delivering a sustainable solution. Just like a factory may have mechanisms and machinery to optimise the delivery of an item on a production line, if we are truly intent on creating a sustainable ‘product’ (i.e the built environment), it necessitates a sustainable ‘process’ that negates waste, redundancy and optimizes efficiency. For our ALICE project in Singapore, a multi-tenanted smart eco-business park, we were able to work closely with the contractor in a design-and-build solution that was completed in 2018, which also received a Green Mark Platinum accolade.

Alice Project

MoL: How do you incorporate the use of media (e.g. television series, books, keynote talks, etc…) to share your knowledge of and research on architecture and sustainably-built environments?

JP: Its interesting that you ask ‘how’ as opposed to ‘why’! Permit me to answer ‘why’ first. We need to be able to spread the information about the cataclysmic effects of climate change as quickly and effectively as possible if we are to educate civil society and preserve the planet for future generations. I have had the privilege of a rounded education that balances the ability to teach and design. This puts me in the fortunate position to relay green messages through oratory, graphic, or literary means. This means I can touch a broader spectrum of society through my lectures, books or my TV series that touches upon either our research or design projects. As for the ‘how’, it is a perpetual cycle. The research that we do feeds our design projects and thus the evolution of our studio; this needs an outlet that often starts as a lecture to one of the Universities that I teach at; and then this becomes a book. The book is then transposed into a TV series for broader consumption. Etc…

MoL: You designed the first zero-carbon house in Asia. Since its development, has the demand for zero-carbon houses in Asia increased? How does this development compare globally?

JP: Soon after setting up Pomeroy Studio, a client, who had seen what I did at the first zero-carbon home (the Idea House), and wanted something similar. This led to B House: Singapore’s pioneering carbon-negative home that was completed in 2016. Not only does it generate more energy than it consumes – (making it carbon-negative) but it costs the same as a traditional property in the same area. This led us to thinking of whether zero carbon developments could be deployed in the Philippines, where there needs to be an even greater economic conscientiousness; and Sweden (the Candy Factory Residences), where the extremities of cold sub-arctic temperatures provided further environmental challenges. I’m delighted to say that in all these cases we were able to create ground breaking zero-carbon homes that were sensitive to culture and climate. They have spawned a number of similar projects that draw inspiration from passive design techniques employed by their ancestors, while incorporating modern green technologies to enhance our daily lives. Thankfully, more and more individuals and companies are coming to realize that the economic fundamentals of green design are sound. The buildings that we create are more efficient, use less energy and are quicker to build through techniques such as modular construction.

B House

MoL: Often, having a certain amount of privilege or wealth is associated with the accessibility of these types of homes. What role do affordability and accessibility play in the demand for sustainable residential buildings? Do you see a future where people of all socio-economic levels will be able to live in these types of homes?

JP: There still remains the perception that sustainability is somehow more expensive and available only to those privileged enough to afford it. Architects and designers who perpetuate that going green costs more are not getting the basics of sustainable design right; developers are therefore having their judgment clouded by green projects that have suffered at the hands of those who simply add costly green technologies to provide a ‘greenwash’ over conventional building designs. Which is why we take pride in being able to prove through our evidence-based sustainable design approach that a green building is actually a cost-efficient building. Why? Because by applying building physics we can shape our designs to enhance air and light to help reduce initial capital costs and onward operational costs; use locally sourced materials to reduce economically and environmentally costly shipping of products, and ensure the design meets institutional standards to safe guard asset class value. We designed a housing community of 246 units in the Philippines that, when completed in 2022, will result in carbon-zero homes at a price point that will be accessible to the average Filipino homeowner where the occupants will never have an energy bill for the rest of their lives given the solar roofs. When people start to see real physical proof that sustainable design is cost-effective, then mindsets will change.

MoL: How has the onset of COVID-19 influenced your work? Have the significant effects of the virus caused you to shift your mindset on how our environments are built? If yes, how so?

JP: There have been pandemics in the past, and there will be more pandemics in the future. Thankfully, we, like our built environments, are remarkably adaptable and resilient, and it is with hope that we will continue to be so for the benefit of our future generations. The design and research that we have undertaken has been, and continues to be, resilient in spite of the Covid-19 cataclysm, and our 6 pillars of sustainable design approach address Covid-19 thus:

Social Balance: The pandemic will not stop our need for co-presence. We will need to learn to balance periods of ‘stepping-out’ to the great outdoors with the need to periodically ‘step-back-in’, in a more responsible manner

Cultural Balance: The pandemic will not stop our need to express ourselves through the arts. We need to balance how we converge in decentralised, local cultural arenas with more global, virtual cultural experiences

Spatial Balance: (De)densification strategies should be phase-able according to the circumstances; balanced with decentralisation strategies that look at alternative opportunities for urban regeneration

Environmental Balance: The hermetically sealed glass box needs to be balanced, if not challenged, by more porous, naturally-ventilated and lit spaces for the health and well-being of our natural and man-made environment

Technological Balance: We should embrace new technology sparingly, and balance with the knowledge that some of the best lessons in combating the pandemic are low-tech solutions that have stood the test of time

Economic Balance: The pandemic may have affected our economic growth near term, though long term we will need to learn to balance global connectivity with local self-sustenance if we are to be more resilient

MoL: Being such a busy person, how do you find the time to prioritize the most important and essential things in your life such as family, friends, and personal self-care?

JP: It’s all about discipline. I still manage 8 hours sleep a day; eat healthily (though I do like a good bordeaux) and exercise every day; despite my hectic schedule. What spurs me to be so disciplined is the look on my children’s faces in the morning. They are the eternal ‘bright star’ optimists who have no worldly worries and are an inspiration to me to live a happier life. Fatherhood is not without its challenges but it has nevertheless been a humbling and fulfilling experience in the same instance. My son is super active so I’m hoping he will follow in Daddy’s footsteps into rowing, rugby and/or martial arts. Another indulgence is the self-imposed ‘solitary confinement’ with the Financial Times Weekend newspaper and its plethora of supplements. If I’m in Venice, I am in heaven at a simple café with a Café Longo with said newspaper; if in London at my favourite pub in front of the fire with, again, the said newspaper. If in Singapore it is at Bacha Coffee café with the pink paper. Time is a simple pleasure yet a precious commodity that I use to gain knowledge, absorb, and reflect and what life has to offer.

MoL: Do you practice a sustainable lifestyle? If so, how?

JP: I live in a condominium on a high floor that faces onto Marina Bay in Singapore. This may not sound sustainable but on the contrary, it is a demonstration of compact inner city living that means that I can walk everywhere, use public transport, open my windows to appreciate the breezes (thus reducing the need for air conditioning) and optimize natural light (thus reducing the reliance on artificial lighting). All of these acts contribute to reducing my carbon footprint. The sense of community in my condominium is remarkable and every weekend it is a joy to bump into neighbours either at breakfast time with my daughter in the café on the ground floor, swimming with my son and his friends in the pool on the 8th floor, or socializing with the other parents over a glass of wine in the skycourt on the 44th floor.

MoL: What advice would you give to someone who wants to become a sustainable architect?

JP: Firstly, be sure you want to be an architect. It is an arduous journey that takes years to qualify and when you do, it may not lead to the projects that you aspired to be doing. It takes guts, tenacity and self-belief to make it in any creative industry; but knowing that you have spent so long studying for the ‘noble’ profession compounds the issue. But when you have decided to be an architect, be sure that you will make a difference that can help shape the places of the future. I still get a buzz when people thank me for the place that they are living, working, playing, learning or connecting in. You will have to commit 100 percent of your life and soul to making a difference, as there is no time to lose: prior to COVID-19, we were consuming 86 million barrels of oil on a daily basis, which was equivalent to filling 5 pyramids of Giza every day. That’s a lot of consumption. And when you consider an ever-increasing global population that will exceed 9 billion people by 2050, consumption (and our carbon emissions) will be on the increase. With such an increase come the cataclysmic environmental consequences of an increased frequency of floods and droughts. So, ‘go green’ to reduce carbon emissions by ensuring that everything that you design reduces, re-uses, recycles and regenerates whatever you touch.

Photography courtesy of Jason Pomeroy

Steven Peck is dedicated to creating greener, healthier & resilient cities with nature & urban agriculture.

Leading sustainable architect working on scalable innovations to deliver on Google’s 2030 Carbon aspirations and the hybrid future workplace.

Arno Adkins is Partner at COOKFOX, an architectural studio dedicated to integrated, environmentally responsive design.