Justin Brice – Environmental Artist

Environmental artist Justin Brice encourages others to take a critical look at the relationship between humans and the planet.

USA

Eva Baron April 9, 2021

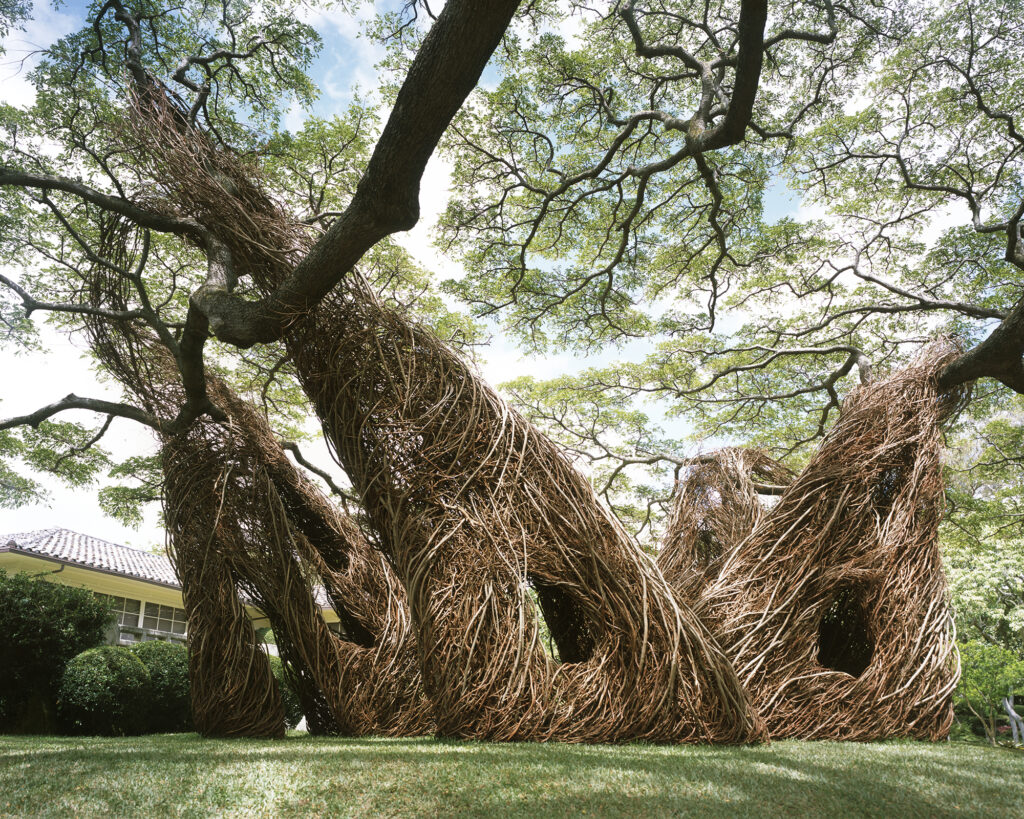

Synthesizing sticks, saplings, and plants, the sculpture artist Patrick Dougherty’s natural-wood installations speak to the complexities of our environment. Since his debut with Maple Body Wrap at the 1982 North Carolina Biennial, Dougherty has created over 300 site-specific, environmental monuments, all of which combine his carpentry skills with his passion for naturalistic structures. His sculptures have gained global as well as local recognition, and he has received various awards, including the 2011 Factor Prize for Southern Art, Henry Moore Foundation Fellowship, and National Endowment for the Arts Fellowship.

Beyond considering a myriad of forms throughout his practice, Dougherty’s work also reveals a striking preoccupation with natural architecture. As tangled webs of huts, cottages, and tunnels, these sculptures encourage direct engagement between audience members and the stick-like architecture that sprouts from our surrounding environment. During a contemporary moment defined by environmental uncertainty and catastrophe, Dougherty and his sculptures offer us a vision into the future, one in which we prove capable not only of coexisting with but living in nature.

Mood of Living: Where are you from? Where did you grow up?

Patrick Dougherty: I was born in Oklahoma but moved to Southern Pines, North Carolina in grade school. My dad practiced medicine and my mother looked after five children. She had artistic tendencies and a yearning to finish her education and become an architect. Our home was flanked by wooded areas and our favorite playground became a dogwood grove where we hollowed out living thickets to make bedrooms, kitchens and more. These early forays into building simple shelters probably influenced my choice of materials when I turned to sculpture as an adult.

MoL: Where are you currently based as an artist?

PD: I currently live in Chapel Hill, NC, where, during the back-to-the-lander days with Mother Earth News and the Foxfire Books in my head, I built a log cabin. Such an endeavor honed my woodsman skills and made it easier to imagine returning to the University of North Carolina to study art and launch a career as a traveling, working sculptor.

MoL: What inspired you to become an artist?

PD: My whole effort to become a sculptor as an adult dovetailed with a secret childhood dream to become an artist. It may have been my mother’s personal struggle with her education that lit the fuse, but I loved to make things. Picking up a stick back then and bending it seemed to give me big ideas, and, when grown, I capitalized on those childhood urges. In addition, my dad, with his commitment to rural health, embodied selfless outreach and personal engagement. His modeling helped me to craft my own sculptural efforts toward engagement with the viewing public. Early on, I began to include volunteers from the local community as part of my construction plans, and I also maintained a building site without fences where passersby could stop and ask questions. My time in a community might also include a talk at the local grade school, breakfast with the city fathers, or an evening with the women’s garden club. A provocative sculpture, like a good health plan, is not something our fellow citizens consciously need. That awareness often takes a nudge.

My trajectory or perhaps aspirations for my career were set by a chance conversation with a visiting artist at the local art department. She posited that it was as easy to be a national artist as it was to stay local, but cautioned that the essential ingredient was a desire to be “in the nation.” Subsequently, I was determined to be in the nation, and the first years required hauling trailers full of bundled saplings up and down the eastern seaboard, building sculptures from New York to Miami. As my credibility grew, I was offered greater opportunities and sought partnerships with sponsors around the United States and the world to create bigger-than-life sculptures from saplings.

MoL: Where did you learn your craft?

PD: For children, a stick is an imaginative object; it is a tool, a weapon, or a piece of a wall. I like to think that somewhere in my subconscious there is residual know-how passed on from our hunting and gathering ancestors. Like all children, I was a serious fort builder and capitalized on some of that innate know-how. After college, I served as a hospital administrator in the United States Air Force. As luck would have it, I was stationed in Germany near a military Special Services Center which offered classes as well as the use of a well-equipped craft shop. Under good guidance, I learned to use every tool and tried my hand at furniture, jewelry, clay, and more. In due time, I returned to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and had two formative years in the Art Department. In that era, I struggled unsuccessfully to put my ideas to a number of materials but ultimately rediscovered the saplings along my own driveway.

I had two breakthrough moments. First, I came to understand what birds already knew about twigs—that is, saplings have an infuriating tendency to tangle with everything. This inadvertent catching is the simplest method of joining and can be used to build enormous structures without the aid of rope, nails, or other joining material. Secondly, not only do saplings carry the overtones of the forest, but they are lines with which to draw. This realization encouraged the use of drawing techniques to enhance the surfaces of the objects I constructed. For example, when a pencil strikes a piece of paper, the result is a series of tapered lines. Since saplings are tapered, organizing all the small ends in one direction can give the impression of a flowing motion in the surface. Using larger gestures than a pencil would allow, I was able to imbue the static surfaces with the drawing quality of a winter landscape where the bare branches seem so active and alive.

MoL: What drew you to natural objects, such as twigs and branches, as mediums?

PD: Childhood play is a first introduction to branches as a primary building material and gives rudimentary insight into why some structures stand and others fall over. But as a sculpture student, I wanted to work big and my efforts in clay kept falling over and were impossible to move into a kiln. I began to imagine another kind of “greenware” which would mold like clay in its green state and then harden to hold its shape. A sapling had that potential, and I developed a proprietary interest in all the sweetgum and red maple saplings along the roadways of North Carolina. Since maintenance crews were sent to cut them down, they seemed a ready source for experimentation.

As my appetite grew, I imagined an endless warehouse of material and began copying the phone numbers on “land for sale” signs and then brought larger trucks. As my career began looking up, I gathered saplings on the verge of railroad tracks in Savannah, GA and between warehouses in Madison, WI. When working at the Brooklyn Botanical Gardens, I was given a patch of willow on the edge of the Verrazano Bridge on Staten Island; Hawaii yielded the invasive, strawberry guava; and Kansas had an overrun of rough leaf dogwood and Siberian elm. Louisiana has willow and water moccasins along rivers, and Maine sports redtwig dogwood and cantankerous moose in upland swamps. Currently my supply of saplings is a product of urbanization. As towns and housing development sprawl, there is a small window of time between the forest being cut and the pouring of foundations. My current source is the regrowth of saplings in the vacant lot on the outskirts of most American cities.

MoL: Before becoming an artist, you studied English Literature at the University of North Carolina and subsequently received an MA in Hospital and Health Administration from the University of Iowa. What made you decide to study art history and sculpture?

PD: When my father realized I was serious about a career change, he described my choice as “a documented case of downward mobility.” For me, however, becoming a sculptor was a gateway to the most satisfying career that I could have ever imagined. Fortunately, all the previous education could be folded in and specific knowledge becomes incredibly useful. For example, literature majors not only read for pleasure but strive to understand how words can be employed to transfix the reader. Sculptors have the similar challenge of crafting materials into compelling illusions that cause a passerby to come running. Further, I am forever grateful for my exposure to administration. My trick, if I have one, has been to partner with an organization and use their good will and leverage in the community to organize the logistics of the build. That equates to organizing funding, ordering scaffolding, finding willing volunteers, and locating a sapling supply.

MoL: What advice do you have for someone who’s interested in art either as a hobby or career?

PD: I think of an art career as a long-term event that requires patience and persistence. Given that most people carry a reservoir of raw talent, it’s important to seek out other makers who know the territory and can offer advice and support. My travels have put me in touch with scores of inspiring sculpture professors, art teachers, and craftsmen—all role models who would be delighted to light the way. If your readers don’t already tinker, I hope each of them will grab a bit of the material world and make something—a fanciful object or something they need. The activity of making sculpture has helped me to personalize the world and has provided a gleaming portal to an enhanced life.

MoL: What is your artistic process like? How do you gather materials and what materials speak to you the most?

PD: The process begins with a site visit during which I develop a concept and series of thumbnail sketches while studying the site. When I return for the construction phase, I lay the footprint of the intended work out on the ground. I drill a series of holes along the perimeter and big long saplings are inserted and become the structural base for the work. Scaffolding is set and these larger pieces are manhandled into the intended shapes. It takes three weeks of threading sticks into the surface to festoon the walls and “polish” the forms into a credible sculpture.

Beyond the huge personal pleasure that I gain from working with the simplest materials, I believe that a well-conceived sculpture can enliven and stir the imagination of those who pass. For viewers the pleasure is elemental and beyond politics and financial forces. I like activating public spaces and being part of the world of ideas. Sometimes as a sculpture nears completion, I hear someone say, “I don’t like art, but I like this” and in this statement I imagine that “sculpture” has wormed its way a little closer to everyday life.

MoL: What forms and natural objects inspire the structures of your sculptures?

PD: When trying to find what to build for a particular setting, I look for starting points. As I struggle to understand the location, I might see a word or a title on the newsstand, the outline of a mountain range in the distance, or hear a turn of a phase from a passer-by. The creative state of mind is one rich in connections, whereby words and images can blend and give rise to an inkling of a new idea. Once the overall effort is described, the actual work is shaped day by day as I react to what I see and try to improve the overall effect.

MoL: How has your understanding of the natural world been integrated into the art you create?

PD: I can say that I have always been an environmentalist. I live in a house with a very small footprint and one that is made primarily from recycled materials. I try to be very conscientious about where and how I gather my saplings, usually finding areas that are regularly maintained. I think my work does reverberate with the viewer and bring up positive associates with the natural world. Children are not the only lovers of sticks. In my position, I come in contact with a lot of adult closet stick-gatherers who imagine all kinds of uses from walking sticks to garden bowers.

MoL: As an environmental artist, how do you imagine social responsibility and eco-consciousness? What can others do to lead more sustainable lives?

PD: Our contemporary challenge is how to reconnect and live in harmony with the plants and animals that still share the earth. Sculptures from twigs and other kinds of environmental initiatives are helping with that awareness. My viewers see stick castles, lairs, and nests. They remember moments in the woods with their favorite trees. They tell stories about the Garden of Eden, and secrets about first dates. Some viewers touch the surfaces and talk about the momentum of wind or other natural forces. Although not meant for habitation, these structures foster fantasies of walking away from the geometry of the city dweller and fading back into the forest for a day. It is my conviction that such personal associations link the viewer more keenly to an awareness of the natural world.

MoL: How can we, both as artists and as citizens, combat the urgency of climate change today? How do you address this through your art?

PD: I wish I had answers for all these big questions, but I feel as powerless as everyone else in the face of systemic problems generated by contemporary life. Give up your car? Recycle? Save an iceberg? Adopt a polar bear? The best that I can do is make work that seems relevant to me and incidentally reminisces about the natural world.

MoL: How do you lead an eco-conscious life and how does this influence your art?

PD: Lately my sister Kate Farrell, who is a poet in New York City, and I were discussing our tree-lined beginnings. Afterwards, I wrote in my journal, “Sometimes when I’m working to build a sapling sculpture, repeating the same motion over and over, day in and day out, I’m overtaken by a feeling of serenity and freedom. In those times, I have the longest view. I feel, not only the pleasure of my childhood and its building phase, but I sense the presence of the forests of long ago and feel myself to be part of the largest conversation.”

MoL: How has your artistic process evolved during COVID? How has COVID impacted the way you understand nature as well as art?

PD: I was building a work at the Montgomery Museum of Art in Montgomery Alabama as it became clear that COVID would intervene profoundly in our daily life. I barely finished before the carpet was rolled up. Projects were canceled and I, like everyone else, sequestered. I had been traveling monthly for 35 years and I was shocked to be grounded. A stint at home revealed years of unfinished projects and loose ends. I began working again on my fishpond and planted a new garden. Luckily, after five months, opportunities rebounded and I was off and working again. Sculpture has been a transfixing career and one that has allowed unique access to communities across America. I have harvested saplings by the truckloads and made an equal number of friends. I hope your readers will take a moment to visit my website at www.stickwork.net.

Photography courtesy of Patrick Dougherty

Environmental artist Justin Brice encourages others to take a critical look at the relationship between humans and the planet.

Internationally recognized filmmaker Andrew Morgan focuses on telling stories for a better tomorrow for various film and new media projects.

Throughout his work with Ala Plástica and Casa Río Lab, environmental activist and artist Alejandro Meitin unites social engagement, art, and sustainability.