Andrew Morgan – Documentary Filmmaker

Internationally recognized filmmaker Andrew Morgan focuses on telling stories for a better tomorrow for various film and new media projects.

USA

Audrey Jaber November 22, 2021

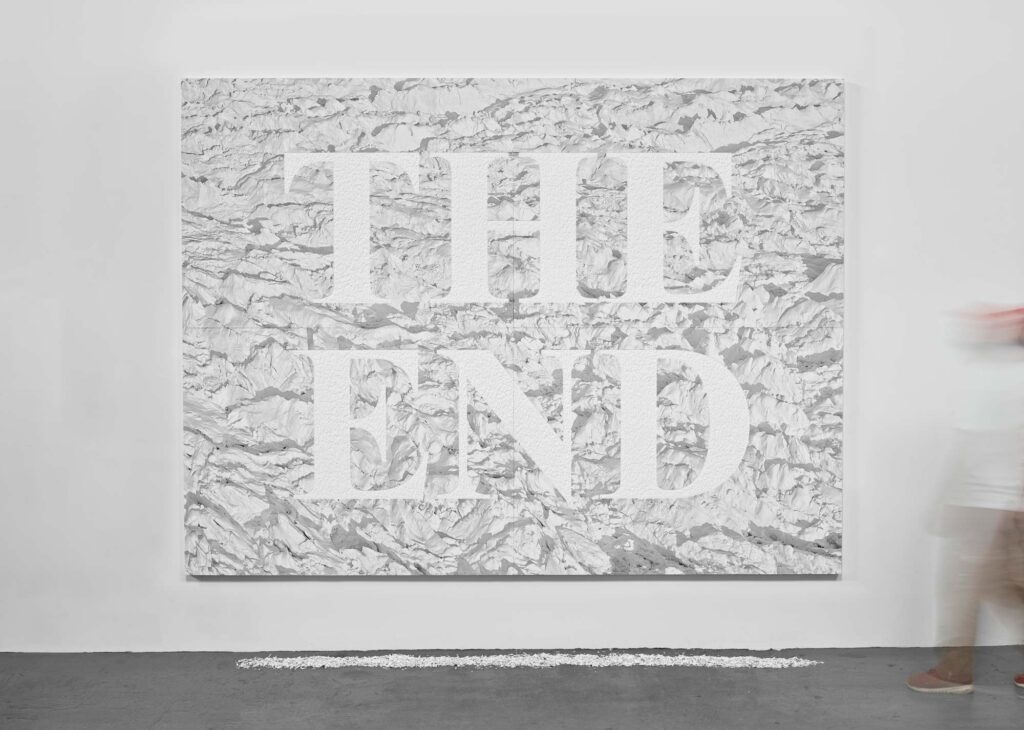

Environmental artist Justin Brice has flown with NASA to document Greenland’s melting ice, created an app to visualize sea-level rise, and had his arm tattooed with a chart of the average temperature of the earth’s surface, all in the name of art. As a visual and conceptual artist, Brice works with an array of mediums, from photography and sculpture to installation art. The common thread throughout all of his work is a focus on the relationship between humans and the natural world.

Born in New Jersey and based in New York, Brice’s work has been featured in cities across the globe, including London, Los Angeles, Venice and Belgium. With messages like “Warning Hurricane Human” and “We Are The Astroid,” his pieces force viewers to take a critical look at their own relationship with the planet.

Mood of Living: Where are you from? Where did you grow up?

Justin Brice: Maplewood, New Jersey.

MoL: Where did you go to school and what did you study?

JB: I studied at several universities, but I was incredibly fortunate to study art history in Venice under the late Terisio Pignatti, and Chinese language and culture in Beijing back in the 1990s. Those were the most transformative bits of my formal education.

MoL: How did studying abroad in Venice and Beijing influence your passion for the environment?

JB: Venice shaped my understanding of art as something to be experienced in a space and place. Pignatti loved art that could be viewed in its original setting within Venice, which was a magical experience. My time in China was very different: it was an onslaught of all the senses. It wasn’t until years later — after traveling extensively for work — did I really begin to understand the ecological impact of what I’d been witnessing across Asia and how it related to the global biosphere. I was part of the problem and felt responsible to do something. I also knew that I had a small platform that I could use to make some noise and call some attention to these issues.

MoL: You previously worked as a photographer and photojournalist in Asia for 20 years, with your work being featured in The New York Times, National Geographic, Time and others. How and why did you make the transition from commercial photography to fine art?

JB: I was never really a commercial photographer. I was a photojournalist and did mostly documentary photography across the region, but I was also always doing my personal projects. My job was to capture what I was observing and forge a visually compelling image that told a story. The primary difference between journalism and art is intention. Over time, I began to feel like I could make a more compelling case to pay closer attention to the natural world through art.

MoL: Where are you currently based as an environmental artist?

JB: I recently moved into the Berkshires, but I still have my studio in Brooklyn and I’m doing more conceptual work which allows me to be out of the studio.

MoL: Why have you chosen to focus your art on the relationship between humans and the natural world? When did you realize that your love for the environment could tie into your artistic talents?

JB: It was a very natural evolution as someone who grew up close with nature, saw the environment declining rapidly all around me and then became a parent. It’s hard not to feel compelled to take some action and do what you can.

MoL: What inspires the ideas behind your public exhibitions?

JB: I’m deeply interested in raising the public consciousness around the issues of ecological collapse, climate change and environmental issues. At the end of the day, they all equate to existential issues and there is no better way to do that than by making public artwork. Art has the unique ability to shift how we see and experience the world around us, and in doing so, shapes culture, which in turn shapes politics and policy. The ecological issues we face are tremendous but don’t let anyone tell you they are not solvable. They simply need broad political will and action.

MoL: Beginning in 2015, you flew on a series of missions with NASA to document Greenland’s rapidly changing ice and used the images as source material in your work. What was this experience like and what did you gain from it?

JB: I was extremely lucky to fly on those flights — it was remarkable. I was up collecting raw materials for my artwork which went into my show “Earth Works: Mapping the Anthropocene” which debuted at the Norton Museum of Art. The greatest thing I personally gained from the experience was witnessing how what we do on one side of the world can directly affect the other side of the world. Everything is so deeply intertwined and interconnected, and I think that’s something we too easily forget in the very localized little worlds that many of us live in.

MoL: What was the inspiration behind “Reduce Speed Now,” your 2019 public exhibition that featured solar-powered LED signs?

JB: I simply wanted to give the public a vocabulary and language to talk about climate change. The idea was to do it in a fun and engaging way. The subject matter is too dark and depressing to be presented in a serious, academic or doom and gloom way, so I took a more dark humor approach. I feel that humor has the ability to disarm and effectively cut through so much crap in a way that nothing else can. The end result was a seriously playful set of eco-haikus flashing on high message boards across New York City, San Francisco, London and many places in between.

MoL: In collaboration with the award-winning app development studios Strange Flavour and Second Verse, you created After Ice, a mobile app that allows users to visualize sea-level rise wherever they are standing via augmented reality. What inspired you to create this app?

JB: This was about making the science of sea-level rise accessible using NASA data, and putting it into the hands of the public in a fun and engaging way. We did it on the fly, with no funding and all volunteers, thanks to the amazing support, guidance and direction of Ian Lynch Smith at Second Verse. I’m currently working on a new AR game about the oceans that is due out in 2022!

MoL: In 2016, when the International Geological Congress voted in favor of formally designating the Anthropocene, you had NASA’s Goddard’s Global Surface Temperature Analysis (GISTEMP) index — which tracked global temperature rise from 1880 through 2016 — tattooed onto your arm. What does this tattoo mean to you?

JB: Let’s just say the carbon record has gotten under my skin!

MoL: What moment in your career as an environmental artist are you most proud of?

JB: It’s not so much pride, but rather that I’m grateful that I can make the work I do because of the support I receive from collectors around the world and my gallery in Brussels. I’m also very grateful for several foundations that continue to support my work. Without these critical pieces to the puzzle, I would not be able to do what I do.

MoL: What is the role of environmental artists in combating climate change?

JB: The artist’s role is absolutely critical and essential. Artists have the ability to transform how we think about, see and experience the world around us. We’re in a bad place ecologically. It’s not so much about climate change anymore — it’s really an existential issue for everyone and everything on this planet. Helping the world see that is one of my primary responsibilities that I’ve taken on while on this planet.

MoL: How do you personally live an eco-conscious life?

JB: Lots of low-hanging fruit things, like LED lights, an electric vehicle and so forth. But our personal consumer choices have little to no impact. Times billions, yes, but the real change happens in the laws we write. So if I can make small changes to how the general public thinks about, or sees the world around them, making them more eco-conscious in the process, that can actually have a real impact. If I can get someone to vote eco-logically (an aphorism from my “Climate Signals” show), that will ultimately have the greatest impact on the survival of our species.

MoL: What advice would you give to someone who is interested in art, either as a hobby or a career?

JB: Art is never a career or hobby — at least I don’t see it in those terms. For me, art is a way of living. It’s a philosophy and a way to live your life. When I think of a “career” or “hobby,” I think of craft-based work.

MoL: Is there anything else that you would like to add?

JB: Yes. To paraphrase the field geologist and palaeontologist Jan Zalasiewicz, it’s important to not forget — We Are The Asteroid.

Photography courtesy of Justin Brice

Internationally recognized filmmaker Andrew Morgan focuses on telling stories for a better tomorrow for various film and new media projects.

Throughout his work with Ala Plástica and Casa Río Lab, environmental activist and artist Alejandro Meitin unites social engagement, art, and sustainability.

As a French fiber artist, Edith Meusnier creates colorful installations with textiles that are exhibited in parks and forests around Europe.