Justin Brice – Environmental Artist

Environmental artist Justin Brice encourages others to take a critical look at the relationship between humans and the planet.

Argentina

Eva Baron May 21, 2021

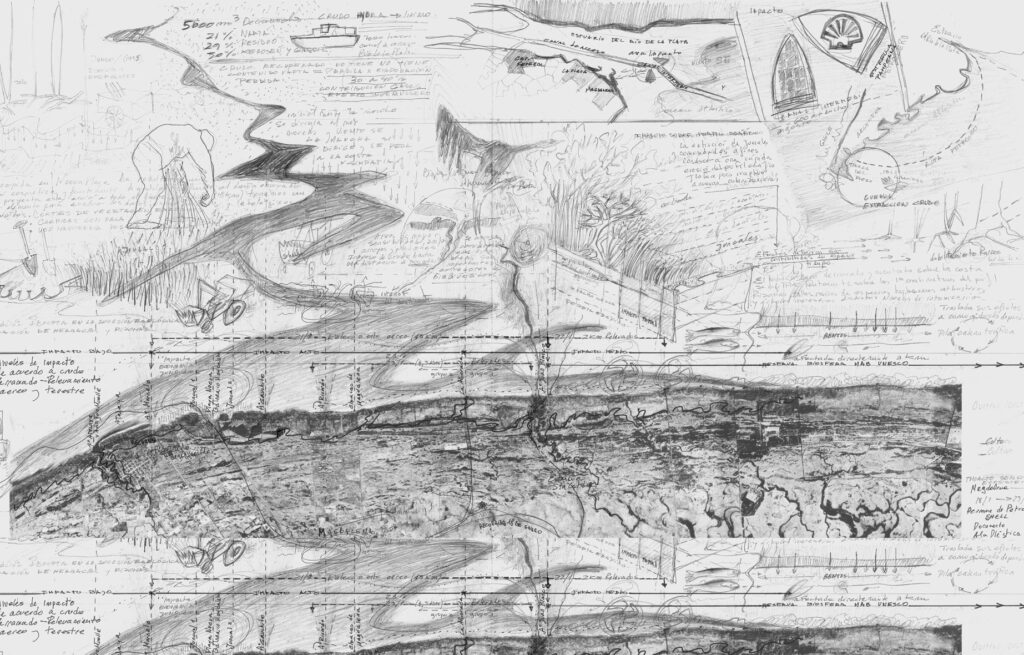

Combining artistic and environmental activism, Alejandro Meitin’s work reflects local politics, landscapes, and communities throughout Argentina and Latin America. Predominantly unfolding in the La Plata region of Argentina, an area characterized by its rivers and basins, Meitin’s interventions concern social transformation and grassroots collaboration in an effort to confront environmental injustice. In 1991, Meitin co-founded Ala Plástica, an art collective that reimagined abandoned spaces into community centers, developed arts education opportunities, and addressed our ongoing climate catastrophe through a myriad of interventions, including Junco/Especies Emergentes (The Reed/Emergent Species). Initiated in 1995, the Junco project involved planting reeds along the La Plata River to create new ecosystems while simultaneously cleansing existing ones. By inviting the local community to participate in the planting process, Ala Plástica successfully bolstered both artistic engagement as well as a deeper understanding of the environmental changes unfolding throughout the La Plata basin.

More recently, however, Meitin founded Casa Río Lab, an organization dedicated to innovative approaches to environmental activism, art, and research. As an interdisciplinary network that connects political actors, scientists, artists, and activists, Casa Río Lab has produced research, exhibitions, workshops, and other interventions that highlight the complex environmental issues at the heart of the La Plata region.

Mood of Living: Where are you from? Where did you grow up?

Alejandro Meitin: I was born and still live in a very small town called Punta Lara in the area of the southern coastal strip of the estuary of La Plata River, approximately 60 kilometers from the city of Buenos Aires. My childhood was marked by my connection with coastal landscapes and its people. The river was like a school for me and I had the great fortune of meeting older people, all of whom had a very fine-tuned sensitivity to living with nature and taught me to see and contact nature in a loving way.

MoL: Where did you go to school and what did you study?

AM: I got my primary education at the public school in the city of La Plata, the administrative, political, and judicial center of the Buenos Aires Province. It is located 6 miles (9 km) inland from the southern shore of the Río de la Plata estuary. I trained as a lawyer at the university.

MoL: What inspired you to work with art as a form of community-building and liberation? How does your geopolitical context influence the way you understand the role of art?

AM: I think seeing so much social injustice and depredation of nature. I live in the outskirts of the mega-city of Buenos Aires, a place where you can feel the encroachment of the concrete mass under your feet. Pressed against the river, you can see the soft resistance of the natural order as it challenges the walls that try to contain it and, furthermore, generates new territories of life. It was here that I learned that it is important to resist not only as part of the natural process of survival, but in response to a fundamental obligation to transform reality.

My main commitment is to relate to the character’s intuitive, emotional, imaginative, and sensory art, with the development of exercises in the social and environmental. Thus, in the long term, a series of relationships and linkages artistic, sensitive, political, economic, and social success to generate the emergence of transformative actions.

The River Plate Basin at the heart of Latin America’s Southern Cone is specifically challenging. It’s economically very important, just as the Mississippi Basin is for the United States. This basin has become a laboratory to observe the dynamics of the global climate crisis as a result of the large-scale exploitation of resources in this region over the past decades. The role of the watershed as a global provider of mineral and food commodities is reconfiguring the whole region which contains cities with large, urban metropolis areas like Buenos Aires, but also is empowering medium size cities like Curitiba, Brazil or Rosario, Argentina.

So this brings together a series of issues that are closely related to the topic of watershed geopolitics. I am particularly interested in investigating the linkages of these large basins with the European and Asian markets. I am also interested in the political dynamics that occur in Latin American territories which are directly influenced by global economies and extractive industries.

These controversies are creating renewed connections between the local and the global parties or allies, mutually influencing them and scaling the regions to a new geopolitical role.

As an artist I have focused my work on these urgent issues asking a series of linked questions: What exercises of political imagination should we perform? Who designs the territories and for whom are they designed? What does “human ecology” mean? How can we include ourselves in the ecological tissue as human beings?

MoL: What is Casa Río Lab, and how has this initiative created a network of cultural and artistic exchange?

AM: Casa Río: Laboratorio del Poder Hacer (River House: Building Power Lab) is a centre of research, exchange, training, and learning located between the Río de la Plata Estuary and the university city of La Plata. It is a place for research into concrete practices—an experimental lab for ‘building power’—whose work starts with the immediate local area but extends to broader issues of land use and political ecology.

At this time Casa Río is made up of a group of artists, lawyers, cartographers, architects, biologists, and young computer scientists. It is specifically focused on working on micro but also macro-political issues in the form of a research study with artistic tools.

In 2018 we became part of a large-scale initiative called Humedales Sin Fronteras [Wetlands Without Borders] that is integrated by regional nodes and organizations in Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, Argentina and the Netherlands. Together we are working on global and bioregional axes on several issues, all of which are focused on the La Plata Basin area.

By inviting political actors, community actors, and scientists into this bioregional initiative we are incorporating the perspective of artistic practice and social transformation onto large-scale dimensions with a geopolitical analysis. The idea is that the distinctiveness of these types of networks—of organizations that can function in many parts of the world—that work in the form of regional alliances have real impact on decision-making processes.

MoL: Prior to founding Casa Río Lab, you spearheaded and worked with the collective Ala Plástica. What were the guiding principles of Ala Plástica, and how did this organization unite art, education, and environmentalism?

AM: Ala Plástica was an art and environmental organization that worked on the rhizomatic linking of ecological, social, and artistic methodology, combining direct interventions and defined concepts to a parallel universe without giving up the symbolic potential of art. Since 1991, Ala Plástica developed a range of non-conventional artworks, focused on local and regional problems, and in close contact and collaboration with other artists, scientists and environmental groups.

Ala Plástica took an intuitive, emotional, and phenomenological approach to a variety of artistic initiatives that affect communities and the environment while promoting the potential of art to transform. The Ala Plástica work can be presented as a concrete example of the methods, organizational structures, aesthetic forms, and social results of a series of artistic processes that are intimately linked to a territory: the estuary of Rio de la Plata.

Utilizing dialogue and communication as primary means, we created unconventional artworks that have regenerated economic networks by retraining individuals in artistic occupations and stimulated collective experiences to empower individuals to have a wider field of influence in their own political and biological environment. Through these processes, our work often was merged into self-organizing strategies that utilize art to re-imagine territories as a vital aspect of community.

MoL: Before being transmuted into Casa Río Lab, Ala Plástica staged a variety of artistic and environmental interventions. Which project was most significant to you and why?

AM: There have been several interesting actions but Junco: Emerging Species (1995) is the most valuable for me. With it, we abandoned the localized approach of urban bubbles and were able to enter the ecosystem vision of large bioregions.

In December 1995, Ala Plástica gave way to a bio project on the west coast south of Rio de la Plata. The artistic exercise consisted of a species recovery emerging from reeds, with the objective of sustaining the coastal ecosystem disrupted by human impact. With the collaboration of the Department of Botany, Faculty of Natural Sciences, and Museum of the Universidad Nacional de La Plata, plus advice from the specialist degree in Botany aquatic plants, Nuncia Tur, an investigation was started on the species—Schoenoplectus californicus—that grows on the coast of the river.

The idea of the project was the recovery of a space and a particular natural system since the emergence of these types of reeds provokes the creation of new territories by sedimentation and by encouraging the establishment of other species. On the other hand, the natural purification and cleansing capacity of these plants is achieved through their absorption of water. The propagation system of these reeds also rapidly colonize the soil through underground rhizomes, forming a network of roots and shoots that extend horizontally.

The concept outlining our drafts was very rich: sedimentation helps create purified worlds. The natural communication and collaboration tissues of the reeds became symbolic of our unconventional artistic exercises. Since then, these values became the foundation of all initiatives of Ala Plástica.

MoL: How does Casa Río Lab revolutionize environmental and community-based art? How does Casa Río Lab build upon Ala Plástica’s framework?

AM: I believe that one of the fundamental aspects of Casa Rio and that has been influenced by Ala Plástica is that we not only work on contexts but also create contexts to achieve transformations.

At Casa Río Lab, like Ala Plástica, we never focus on thinking about our practices as projects, since the idea of “projecting” (in Spanish the verb “proyectar” means “to plan”) presupposes a fixed objective or goal that’s defined beforehand. This would constrain the potential of our interaction with the social groups that we engage as well as the unexpected developments generated by the interchange itself. We prefer to speak of “initiatives,” and within them of various “exercises” that multiply, involving people and groups with whom we establish dialogues and develop actions based on principles of reciprocity.

MoL: What does site-specificity mean to you and how do you get to know the communities in which you work? How does community engagement impact your work?

AM: Communities are identified by systems that are environmentally recognizable. The integration of a place’s symbolic role and the forms built in the natural landscape—such as architecture—has been represented by art in most cultures. This commitment to the empirical specificity of the site and the situation is essential for the work of making local knowledge visible.

In our practice, art is an integral part of a shared working process, produced jointly or in negotiations with groups, activists, associations, and more. Communities are formed where the participants’ immersion in this process of creation is converted into the central material and constitutive core of the work. This involves a social collective or, sometimes, the entire population of a specific region, ultimately staging micro-utopias of human interaction. These constitute a cultural movement focused more on social creativity than on self-expression. The work is then constituted as an ensemble of forces and effects that operate in numerous registers of meaning.

MoL: How do community-based art and education serve as tools of liberation?

AM: I think that this form of art holds the possibility of developing a new objectivity that grows based on cooperation. The artwork installed in this way emerges in the experience of collective life and creates new possibilities for imagination. In this way, it is possible to mobilize feedback and interdependencies that activate the imaginary and encourage human action regardless of causes and reasons of a purely logical nature.

MoL: As an artist, environmental activist, lawyer, and educator, how do you integrate social responsibility and eco-consciousness throughout your work? What can others do to lead more sustainable and ethically engaged lives?

AM: Engaging thought with action and with sensitivity to the world and the relationships within it. I believe that any area of knowledge must be coexistent with the ecosphere in such a way that cultural values are not separated from ecological ones. It is simply necessary to understand that the environment—both its cultural and natural manifestations—is only an extension of who we are.

MoL: How do you lead an eco-conscious life and how does this influence your art?

AM: Supporting causes that I consider just, analyzing toxic and harmful behaviors like competitive self-assessment—which are extreme burdens that do not amount to more than a waste of time—and moving away from the egocentric visions that are deeply ingrained in our existence.

All of these efforts directly influence my understanding of art and allow me to integrate creativity as a unifying element in social, environmental, and economic processes.

MoL: What advice can you give to the next generation of artists, educators, and activists committed to sustainability and social justice?

AM: The challenge is to advance the causes that one believes and trust in it while constantly strengthening one’s values and distancing oneself from one’s “anti-values.” But hey, these are searches that everyone has to do in their own lives.

MoL: How has your artistic process evolved during COVID? How has COVID impacted the way you understand nature, art, and community engagement?

AM: The impact has been severe, in particular with regard to personal ties. But at Casa Río Lab, we have developed several analog and digital online communication devices that allow us to keep our networks active. Among them is the collaborative cartography that we have developed together with the philosopher, artist, and cartographer Brian Holmes and a group of young computer scientists and communicators. The cartography is a visualization exercise that aims to create knowledge and enhance the collective processes of territorial integration, giving advantage to the emergence of new visions from the peoples and the activities that support the network of life, allowing for the emergence of new symbolic, environmental, and organizational practices.

My work, though, is not focused on the realization of a work of art to be exhibited at the conclusion of a project. The focus of the work is instead oriented to catalyze social creativity rather than simply self-expression. Although in some cases the results of my work, or that of the groups that I have formed, have been exhibited in galleries or museums, this was never the destination for which they were conceived.

Photography courtesy of Alejandro Meitin

Environmental artist Justin Brice encourages others to take a critical look at the relationship between humans and the planet.

Internationally recognized filmmaker Andrew Morgan focuses on telling stories for a better tomorrow for various film and new media projects.

As a French fiber artist, Edith Meusnier creates colorful installations with textiles that are exhibited in parks and forests around Europe.